Sid Singaravel

Graduate Analytics @ Northeastern, MA

Previously, Data Science @ Fidelity, ZoomRx

Otherwise - cooks, runs, fantasy football.

📧 singaravel dot s at northeastern dot edu

LinkedIn | GitHub | Substack | Tableau

📄 View my résumé

Simulating the Monty Hall Problem

“Suppose you’re on a game show, and you’re given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say No. 1, and the host, who knows what’s behind the doors, opens another door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, “Do you want to pick door No. 2?” Is it to your advantage to switch your choice?”

The Monty Hall Problem is one of the most famous probability puzzles, and it beautifully demonstrates how counterintuitive probability can be. Let’s break it down in a fun and simple way! 🎯 The Setup

You’re on a game show with three doors: Behind one door is a shiny new car 🚗. Behind the other two doors are goats 🐐🐐. You pick a door (say Door 1). The host, who knows what’s behind all the doors, opens one of the other two doors to reveal a goat. Now, you’re faced with an important question:

Do you stick with your original choice or switch to the other unopened door?

🤔 The Intuition Trap

At first glance, it might seem like it doesn’t matter whether you switch or not. After all, there are two doors left, so isn’t it a 50-50 chance? Nope! This is where probability plays its sneaky tricks. If you switch, your chances of winning the car jump to 67.4%, while sticking gives you only a 32.6% chance. Why? Let’s break it down.

🧠 Why Switching Works

Initial Choice Probability: When you first pick a door, there’s a 1/3 chance you picked the car and a 2/3 chance you picked a goat. Host’s Action: The host always opens a door with a goat, which gives you extra information about where the car might be. Switching Logic: If your initial choice was wrong (2/3 chance), switching will lead you to the car. If your initial choice was right (1/3 chance), switching will lead you to a goat. Since there’s a higher probability (2/3) that your initial choice was wrong, switching maximizes your chances of winning.

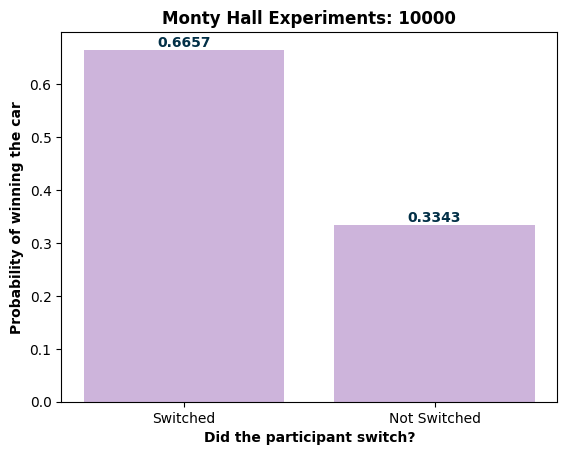

📊 Simulation Results

The chart above shows the results of simulating this problem 10,000 times: When participants switched, they won the car about 67.4% of the time. When they didn’t switch, they won only about 32.6% of the time. This confirms that switching is indeed the winning strategy!

🚀 Takeaway

If you ever find yourself on a game show faced with this dilemma: Smile at the host 😏. Switch those doors confidently 🚪➡️🚪. Drive off in your shiny new car 🚗! Probability may feel unintuitive at first, but once you understand it, it’s like having a cheat code for life!

TLDR; Always switch.

import random

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

trials = 10000

def montyHall(trials = trials):

counter = 0

doors = ['car', 'goat', 'goat']

for _ in range(trials):

random.shuffle(doors)

# Player's initial choice

choice = random.randint(0, 2)

remaining_indices = [i for i in range(len(doors)) if i != choice]

goatIndex = lambda x: 'goat' in x

goatDoors = [i for i in remaining_indices if goatIndex(doors[i])]

openedDoor = random.choice(goatDoors)

# Switch

[switchedDoor] = [i for i in range(len(doors)) if (i != choice) and (i != openedDoor)]

if doors[switchedDoor] == 'car':

counter += 1

return [round(counter/trials, 4), round(1 - counter/trials, 4)]

out = montyHall()

plt.bar(['Switched', 'Not Switched'], out, color = '#cdb4db')

for i, _ in enumerate(range(2)):

plt.text(i, out[i], str(out[i]), ha='center', va='bottom', weight = 'bold', color = '#023047')

plt.title(f'Monty Hall Experiments: {trials}', weight = 'bold')

plt.ylabel('Probability of winning the car', weight = 'bold')

plt.xlabel('Did the participant switch?', weight = 'bold')

plt.show()